The component designer mandates the required steps of an algorithm, and the ordering of the steps, but allows the component client to extend or replace some number of these steps.

Template Method is used prominently in frameworks. Each framework implements the invariant pieces of a domain's architecture, and defines "placeholders" for all necessary or interesting client customization options. In so doing, the framework becomes the "center of the universe", and the client customizations are simply "the third rock from the sun". This inverted control structure has been affectionately labelled "the Hollywood principle" - "don't call us, we'll call you".

The implementation of template_method() is:

call step_one(), call step_two(),

and call step_three(). step_two()

is a "hook" method – a placeholder. It is declared in

the base class, and then defined in derived classes.

Frameworks (large scale reuse infrastructures) use Template

Method a lot. All reusable code is defined in the framework's

base classes, and then clients of the framework are free to

define customizations by creating derived classes as needed.

| Before | After | |

|---|---|---|

// The SortUp and SortDown classes are almost

// identical. There is a massive opportunity

// for reuse - if - the embedded comparison

// could be refactored.

class SortUp { ///// Shell sort /////

public:

void sort( int v[], int n ) {

for (int g = n/2; g > 0; g /= 2)

for (int i = g; i < n; i++)

for (int j = i-g; j >= 0; j -= g)

if (v[j] > v[j+g])

doSwap(v[j],v[j+g]);

}

private:

void doSwap(int& a,int& b) {

int t = a; a = b; b = t;

}

};

class SortDown {

public:

void sort( int v[], int n ) {

for (int g = n/2; g > 0; g /= 2)

for (int i = g; i < n; i++)

for (int j = i-g; j >= 0; j -= g)

if (v[j] < v[j+g])

doSwap(v[j],v[j+g]);

}

private:

void doSwap(int& a,int& b) {

int t = a; a = b; b = t;

}

};

int main( void ) {

const int NUM = 10;

int array[NUM];

srand( (unsigned) time(0) );

for (int i=0; i < NUM; i++) {

array[i] = rand() % 10 + 1;

cout << array[i] << ' ';

}

cout << '\n';

SortUp upObj;

upObj.sort( array, NUM );

for (int u=0; u < NUM; u++)

cout << array[u] << ' ';

cout << '\n';

SortDown downObj;

downObj.sort( array, NUM );

for (int d=0; d < NUM; d++)

cout << array[d] << ' ';

cout << '\n';

system( "pause" );

}

// 3 10 5 5 5 4 2 1 5 9

// 1 2 3 4 5 5 5 5 9 10

// 10 9 5 5 5 5 4 3 2 1

|

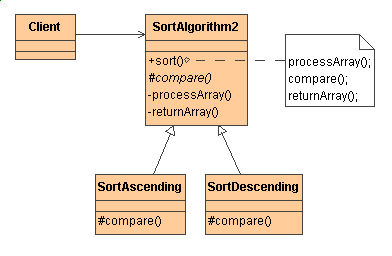

// The common implementation has been moved to

// an abstract base class, and a "placeholder"

// has been defined to encapsulate the embedded

// comparison.

// All that remains for the SortUp and SortDown

// classes is to implement that placeholder.

class AbstractSort { ////// Shell sort //////

public:

void sort( int v[], int n ) {

for (int g = n/2; g > 0; g /= 2)

for (int i = g; i < n; i++)

for (int j = i-g; j >= 0; j -= g)

if (needSwap( v[j], v[j+g] ))

doSwap(v[j], v[j+g]);

}

private:

virtual int needSwap(int,int) = 0;

void doSwap(int& a,int& b) {

int t = a; a = b; b = t;

}

};

class SortUp : public AbstractSort {

/* virtual */ int needSwap(int a, int b) {

return (a > b);

}

};

class SortDown : public AbstractSort {

/* virtual */ int needSwap(int a, int b) {

return (a < b);

}

};

int main( void ) {

const int NUM = 10;

int array[NUM];

srand( (unsigned) time(0) );

for (int i=0; i < NUM; i++) {

array[i] = rand() % 10 + 1;

cout << array[i] << ' ';

}

cout << '\n';

AbstractSort* sortObjects[] = {

new SortUp, new SortDown };

sortObjects[0]->sort( array, NUM );

for (int u=0; u < NUM; u++)

cout << array[u] << ' ';

cout << '\n';

sortObjects[1]->sort( array, NUM );

for (int d=0; d < NUM; d++)

cout << array[d] << ' ';

cout << '\n';

system( "pause" );

}

// 1 6 6 2 10 9 4 10 6 4

// 1 2 4 4 6 6 6 9 10 10

// 10 10 9 6 6 6 4 4 2 1

|

Template Method uses inheritance to vary part of an algorithm. Strategy uses delegation to vary the entire algorithm. [GoF, p330]

Strategy modifies the logic of individual objects. Template Method modifies the logic of an entire class. [Grand, p383]

Factory Method is a specialization of Template Method. [Head First Design Patterns, p311]