new operator considered harmful.

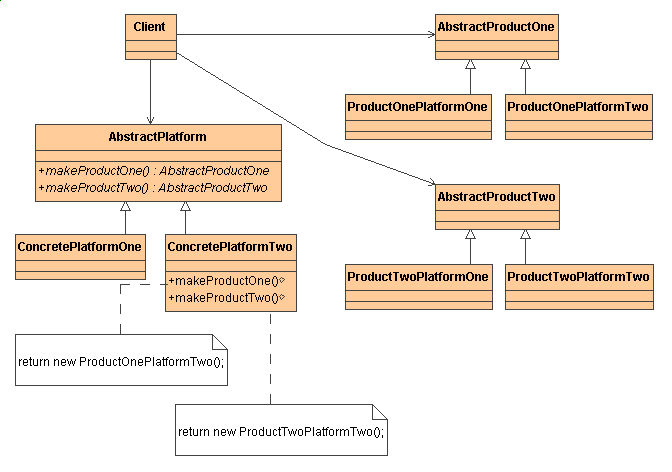

This mechanism makes exchanging product families easy because the specific class of the factory object appears only once in the application - where it is instantiated. The application can wholesale replace the entire family of products simply by instantiating a different concrete instance of the abstract factory.

Because the service provided by the factory object is so pervasive, it is routinely implemented as a Singleton.

new operator and the

concrete, platform-specific, product classes. Each "platform" is

then modeled with a Factory derived class.

new operator.

new,

and use the factory methods to create the product objects.

| Before | After | |

|---|---|---|

// Trying to maintain portability across

// multiple "platforms" routinely requires

// lots of preprocessor "case" statements.

// The Factory pattern suggests defining a

// creation services interface in a Factory

// base class, and implementing each

// "platform" in a separate Factory derived

// class.

// BEFORE - The client creates "product"

// objects directly, and must embed all

// possible platform permutations in nasty

// looking code.

#define MOTIF

class Widget {

public:

virtual void draw() = 0;

};

class MotifButton : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "MotifButton\n"; }

};

class MotifMenu : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "MotifMenu\n"; }

};

class WindowsButton : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "WindowsButton\n"; }

};

class WindowsMenu : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "WindowsMenu\n"; }

};

void display_window_one() {

#ifdef MOTIF

Widget* w[] = { new MotifButton,

new MotifMenu };

#else // WINDOWS

Widget* w[] = { new WindowsButton,

new WindowsMenu };

#endif

w[0]->draw(); w[1]->draw();

}

void display_window_two() {

#ifdef MOTIF

Widget* w[] = { new MotifMenu,

new MotifButton };

#else // WINDOWS

Widget* w[] = { new WindowsMenu,

new WindowsButton };

#endif

w[0]->draw(); w[1]->draw();

}

int main( void ) {

#ifdef MOTIF

Widget* w = new MotifButton;

#else // WINDOWS

Widget* w = new WindowsButton;

#endif

w->draw();

display_window_one();

display_window_two();

}

// MotifButton

// MotifButton

// MotifMenu

// MotifMenu

// MotifButton

|

// AFTER - The client: creates a platform-

// specific "factory" object, is careful

// to eschew use of "new", and delegates

// all creation requests to the factory.

#define WINDOWS

class Widget {

public:

virtual void draw() = 0;

};

class MotifButton : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "MotifButton\n"; }

};

class MotifMenu : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "MotifMenu\n"; }

};

class WindowsButton : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "WindowsButton\n"; }

};

class WindowsMenu : public Widget {

public:

void draw() { cout << "WindowsMenu\n"; }

};

class Factory {

public:

virtual Widget* create_button() = 0;

virtual Widget* create_menu() = 0;

};

class MotifFactory : public Factory {

public:

Widget* create_button() {

return new MotifButton; }

Widget* create_menu() {

return new MotifMenu; }

};

class WindowsFactory : public Factory {

public:

Widget* create_button() {

return new WindowsButton; }

Widget* create_menu() {

return new WindowsMenu; }

};

Factory* factory;

void display_window_one() {

Widget* w[] = { factory->create_button(),

factory->create_menu() };

w[0]->draw(); w[1]->draw();

}

void display_window_two() {

Widget* w[] = { factory->create_menu(),

factory->create_button() };

w[0]->draw(); w[1]->draw();

}

int main( void ) {

#ifdef MOTIF

factory = new MotifFactory;

#else // WINDOWS

factory = new WindowsFactory;

#endif

Widget* w = factory->create_button();

w->draw();

display_window_one();

display_window_two();

}

// WindowsButton

// WindowsButton

// WindowsMenu

// WindowsMenu

// WindowsButton

|

Abstract Factory, Builder, and Prototype define a factory object that's responsible for knowing and creating the class of product objects, and make it a parameter of the system. Abstract Factory has the factory object producing objects of several classes. Builder has the factory object building a complex product incrementally using a correspondingly complex protocol. Prototype has the factory object (aka prototype) building a product by copying a prototype object. [GoF, p135]

Abstract Factory classes are often implemented with Factory Methods, but they can also be implemented using Prototype. [GoF, p95]

Abstract Factory can be used as an alternative to Facade to hide platform-specific classes. [GoF, p193]

Builder focuses on constructing a complex object step by step. Abstract Factory emphasizes a family of product objects (either simple or complex). Builder returns the product as a final step, but as far as the Abstract Factory is concerned, the product gets returned immediately. [GoF, p105]

Often, designs start out using Factory Method (less complicated, more customizable, subclasses proliferate) and evolve toward Abstract Factory, Prototype, or Builder (more flexible, more complex) as the designer discovers where more flexibility is needed. [GoF, p136]